Forum Replies Created

-

AuthorPosts

-

yuta @yuta

As you rightly pointed out, there is often a claim that the overtone series provides a basis and the overtone series may serve as a “a piece of the puzzle” of tendency. However, many issues remain unresolved. Chief among them is how to explain the minor scale.

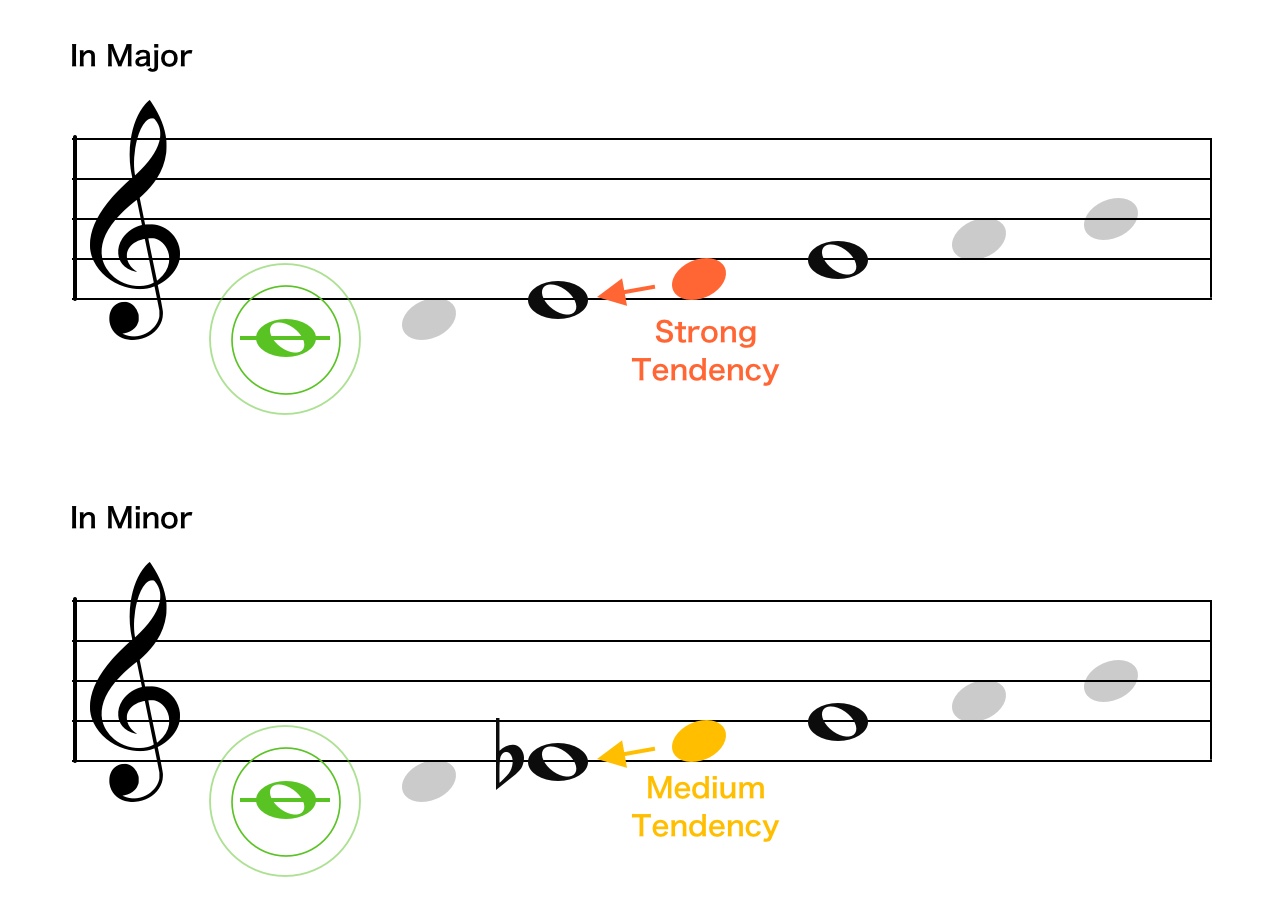

Taking the C minor scale as an example, in this scale, the F note is considered to have less tendency because both neighboring notes are a whole tone away. (This is actually mentioned in “Great Songwriting Techniques” too.)

However, purely in terms of the relationship between F and the tonal center, which is C, this remains consistent with the major scale; F is still distantly related as the 21st overtone.Thus, we can see that a change in tendency occurs depending on the neighboring tones. Therefore, it becomes evident that the concept of tendency involves the entire structure of the scale and cannot be simply explained by the frequency ratios or the overtone order of just two tones (a tone vs the center).

Similarly, in the C minor scale, A♭ exhibits a strong tendency while F with a medium tendency. But comparing their order in overtone series, A♭ is the 13th (though large errors are acknowledged) and F is the 21st. Here, the pattern is reversed and the law is disrupted.

Another question arises: If the overtone series were the sole determining factor, wouldn’t it be contradictory if the ti♭ (the 7th overtone) or fa♯ (the 11th overtone) were not stable?

Of course, non-diatonic tones should not stabilize within diatonic tonality. However, this implies that the specific “context” of tonality, which is not something that exists as physical sound waves, influences our cognition. Therefore, the conclusion remains that explaining everything solely through the overtone series will not work. Things are not that straightforward.What I believe to be an appropriate understanding at this point is; the tendency theory relies on the highly fundamental “axiom” of chord theory that “tertian chords are stable”.

In chord theory, even though the stability of major chords can be theoretically explained by the overtone series, this does not apply to minor chords. This parallels the discussion of tendencies, where hypotheses that work well in a major scale fail in minor.

Currently, theories regarding stability and harmony are being debated as culturally dependent, so it would be premature to hastily conclude tendencies as purely physical properties.yuta @yutaThanks!

I also found a questionable case from Debussy, “Les collines d’Anacapri”:

from 0:30 the main phrase starts. It in the key of B. The phrase consists of B, C♯, D♯, F♯, G♯, A♯; the Omitted-4 B major scale.

from 2:13 the melody appears again, but the left hand plays D♮. The area is very much modal so I cannot clarify the key, but considering that D♯ is replaced with D♮, it’s B melodic minor. So kinda seen as retonalitization to parallel minor key.

The phrase contains D♯ in the later part. In this case, Debussy avoid clashing by using chromaticism. The left hand goes crazily chromatic obviously just before when D♯ and D would clash😂

I believe that the pentatonic-ish-ness (though it’s just omitted-4, not really pentatonic) contributes to blurring the major key qualities from the outset, making it easier to switch the accompaniment to parallel minor in the middle section as a result.

yuta @yutaThanks!!

Again, to the subdominant key.

I think it’s easier to adapt a melody to the subdominant key rather than to the dominant key.

The D♭ major chord is ♭VII if interpreted in Cm key. ♭VII is a very common non-diatonic chord, and sometimes, even playing the note Ti over that chord is acceptable, unless emphasized too much. It could be why the melody fits to the subdominant key this much naturally.yuta @yutaWow, thanks!

The same melody is repeated, but the accompaniment is in Cm key. The opposite pattern as yours; the modulation to the dominant key.

As for the chronological order, it certainly involves a modulation to the dominant key. However, in terms of the actual composition process, the process might be the reverse. I speculate that the melody was originally composed in the key of C minor, and then later adapted as the intro, with the F minor key assigned afterward.

The last phrase “F-G-F-E♭-C” alone evoke me the sense of “re-mi-re-do-la” in Cm more strongly than “la-ti-la-so-mi” in Fm, from my experience. especially taking into account that it’s the finishing part of the intro.In both cases, the melody fits more to either of the two keys; and it can be observed roughly by how stable kernels / shells are assigned to the important notes. I think it would be ideal if a melody fits perfectly to both keys, making it indiscernible which key the melody originally aims at.

Pentatonic scales do have the potential to get re-tonalitized.

Now I think it wouldn’t be surprising if composers from the early 20th century like Debussy, Bartok or Ravel already tried this method, for both the pentatonic scales and polytonality are keywords of that era.-

This reply was modified 1 year, 11 months ago by

yuta.

yuta.

-

This reply was modified 1 year, 11 months ago by

-

AuthorPosts