Contents

1. The Necessity?

Let’s start with the fundamental question : What is music theory?

Some may have doubt on the importance of “theory” in Music.

But this is an unanswerable question—because “music theory” encompasses a wide range of topics, including everything from basic terms like Pitch, Bass or BPM to highly academic orchestration techniques. To lump all of these diverse subjects together and ask, “Is it necessary or not?” is not a properly framed debate to begin with.

It’s like what Math is to us. Few people need differential/integral calculus in their daily lives, but most people can’t live without basic arithmetic operation like 1+1.

So, the purpose of this introduction is not to force an answer to such a vague question. Instead, it aims to help you understand what “music theory” entails, so you can determine whether it is “useful” (not “necessary”) to you at this moment, and “to what extent” you should study it.

2. The Three Layers

“Theory” is, simply put, a well-organized collection of wisdom and knowledge. Therefore, “music theory” is a set of knowledge that aids in creating, playing, and analyzing music.

So, how exactly is this body of knowledge structured? To give you an idea, I would like to categorize the knowledge into three broad layers: Names, usages and manners.

Let’s check them one by one.

The Names

To theorize music, it is necessary to give names to sounds, creating vocabulary to explain the application of sounds.

You may have heard of words like “C minor”, “D7” or “Gsus4″… They are names for chords (= combinations of notes played at a time).

These vocabulary becomes the basis of music theory. More common words like Tempo, Beat, Scale, etc, are also categorized in this area.

Examples of the “Names”

- Verse, Chorus

- Beat, Bar, Time

- Major key, Minor Key

- Stepwise melody, Skipwise melody

- Seventh chord, Ninth chord

- Tonic, Dominant, Subdominant

- …

These words are like the names of colors in painting. True that you can paint a picture without knowing the names for colors, but when it comes to explain the theory of paintings, it must be unfeasible without names. The “Names” layer acts as the very fundamental elements of a theory.

The Usages

But the “names” are nothing but a crowd of names. “G7” is a name of a chord, it doesn’t tell you what musical effect it has, to which scene it fits or what genres like to use it … whatever.

So the next big layer is the “usages” of sounds. The more practical patterns like “This technique is useful when you want to prolong the end of the part” or “This chord is good for creating nostalgic feel” are categorized here.

Examples of the “Usages”

- A chord good to insert right before a chorus part

- A chord that evokes painful emotion

- A scale that sounds Arabic

- A scale that fits for heavy EDM drop

- A melody that adds strong emotional feel to a ballad

- A rhythm that gives relaxed impression

- A rhythm suitable for summer party song

- …

The “usage” layer serves as a toolkit of basic ideas for realizing musical themes and crafting compositions. It encompasses a collection of reproducible techniques that can shape a piece of music in specific ways. This is another role that music theory fulfills.

When several pieces of “usage” knowledge are combined, they can form a comprehensive method for a specific purpose, such as “how to create Halloween-themed background music”. Composers can then utilize this method to compose tracks efficiently.

The “usage” knowledge ranges from general principles to specific patterns. If we were to draw an analogy with language, it might be akin to idioms or syntax. It isn’t about a highly organized system but rather a collection of practical knowledge that enables specific expressions.

The Manners

Say you want to make some specific ethnic music, just using their traditional instruments doesn’t make it sound “real” if its contents are just another popular music.

- Indonesian instruments in pops manner

A genre, or even an artist, has some factors to characterize or define it. It is another role of music theory to analyze and explain them.

Characteristics of a genre are typically represented by a bundle of manners, styles or tendencies. The most famous—or infamous—one is that of classical music, but Jazz, rock, EDM… any music has manners, which can be described using music theory.

Examples of the “Manners”

- A manner of 18th century classical music

- A manner of modern jazz

- A standard format of blues music

- A method for making Hollywood-like film music

- A method for making a fictional traditional music

- Characteristics of Debussy’s songs

- Characteristics of Coldplay’s songs

- …

You can see the “manners” layer as a stack of multiple “usages” to form a larger body of knowledge. Both represent practical knowledge, but while “usage” is useful for specific expressions regardless of genre, “manner” shapes the characteristics of a particular genre.

Names, Names, Names…

The biggest factor contributing to the frustration of learning theory will be the “names” layer. Names are just names, and until you move on to the usage layer, no matter how much you memorize, the names you acquire doesn’t translate into practical skills. This must make you demotivated, just as it is so in learning a new language.

Let me perform an experiment—What if music theory abolished the use of its terminology?

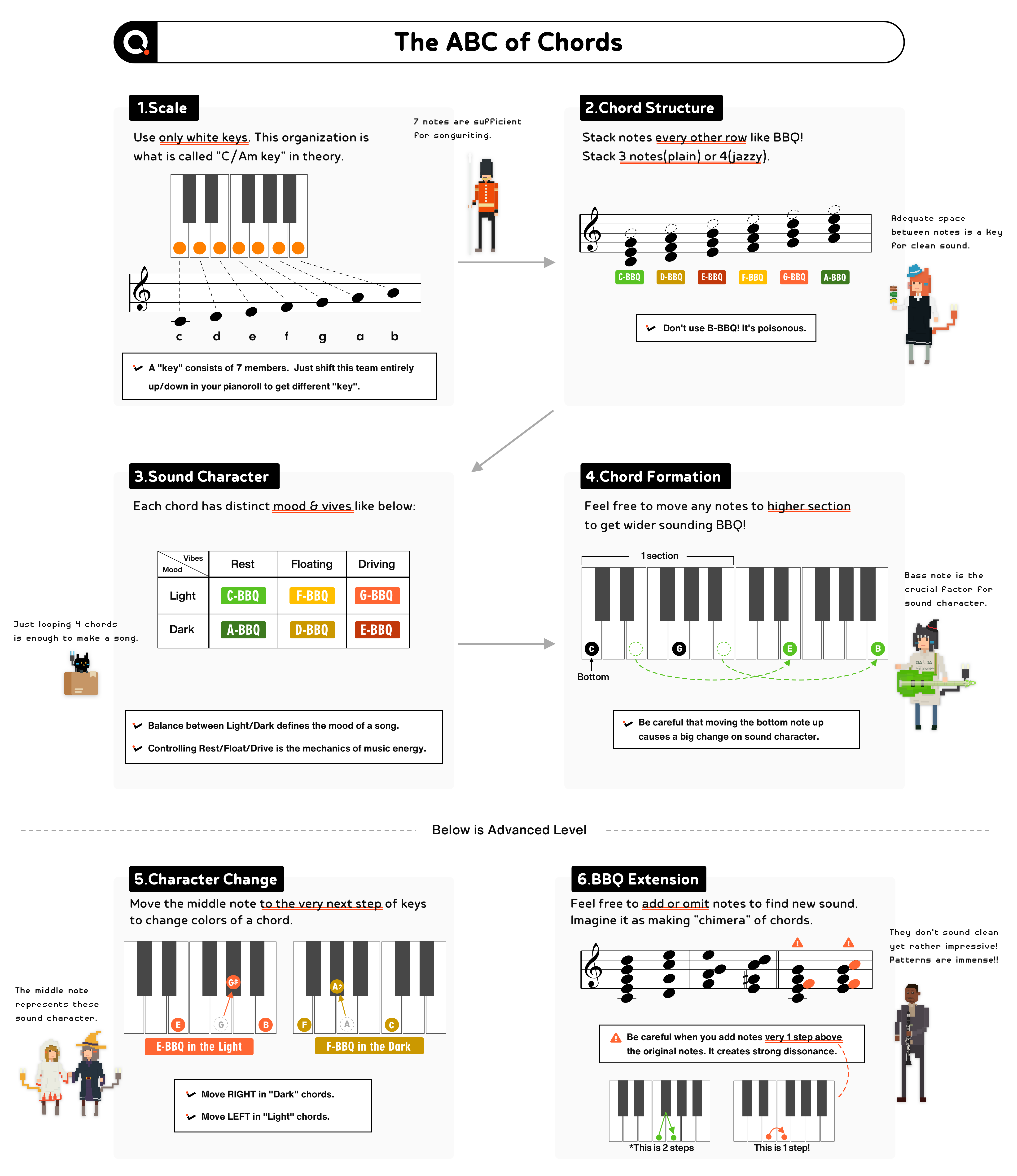

This is just a sheet of paper, but it describes roughly everything in Chapter I of “Chord” part.

With technical terms removed, I think you can read through this paper relatively easily. (Perhaps, this might be adequate for your songwriting!)

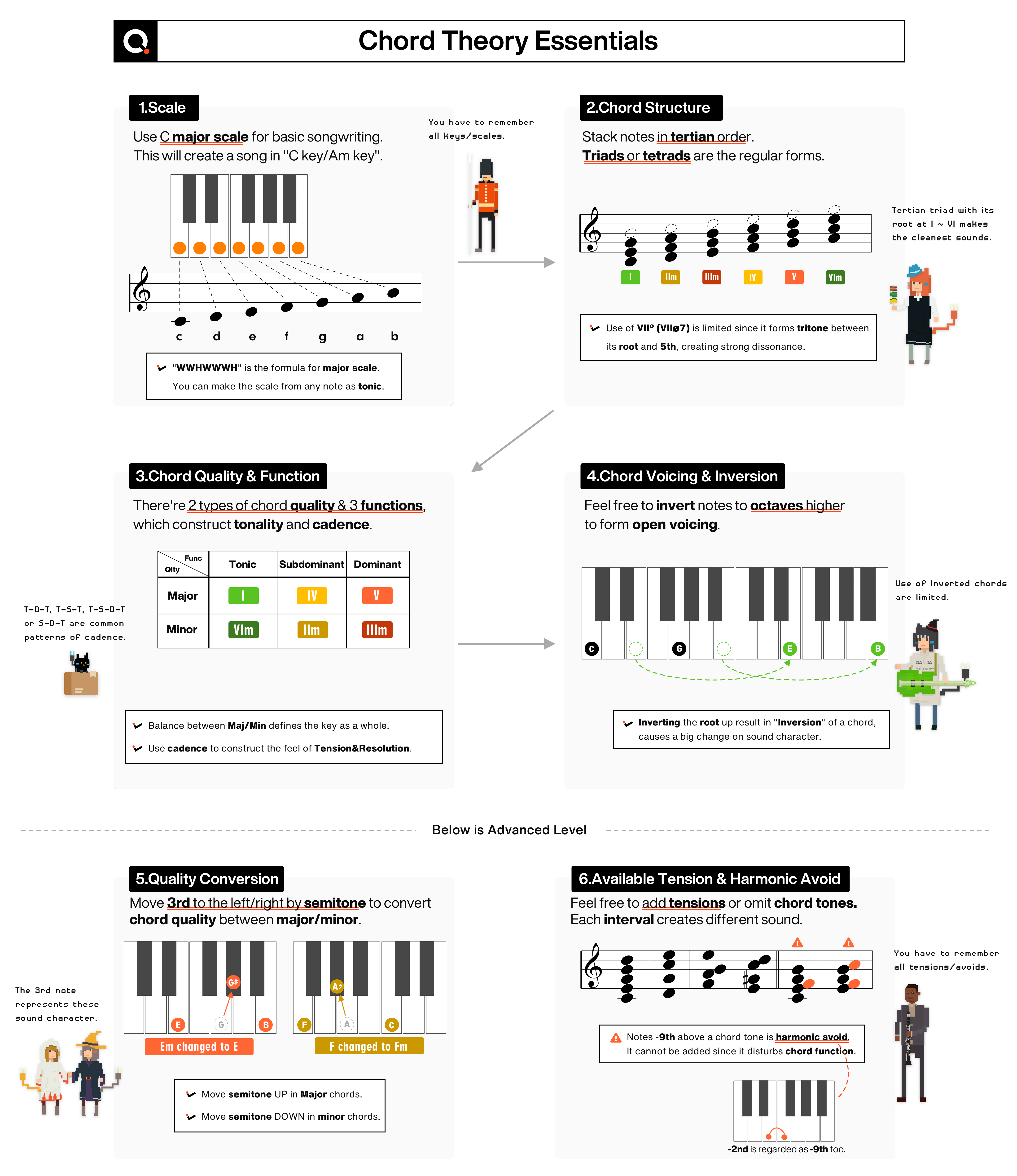

But then go back to the reality. Below is how music theory actually is taught.

Oh welcome to abracadabra world😭😭 Now you can see, The difficulty of music theory lies not in its system itself, but in its explanation filled with terms.

Therefore, your mindset is also crucial here. While “names” are important for organizing information and communication, understanding the “usage” is sufficient for practical composition. It might even be okay to slack off on memorization a bit.

We aim to reduce the burden by spreading out the memorization timing as much as possible and also providing help tooltips to assist you.

3. Theory and Rules

Now you’re starting to grab the whole picture of music theory. You’ll get “Names” of music, good “Usages” of them, and the “Manners” of music you want to make.

So here I want to clarify one very important fact : Music theory is not the rules of music. It’s more like a how-to book that gives you hints about making a specific music/sounds.

Theory never rules reality. On the contrary, it is reality that rules theory. Does economics rules economy? Or does a grammar rules a language? NO, opposite. Theory always follows reality and tries to explain its principle.

Rules… or What?

But you may have heard of the “rules” of music — like “This chord must be followed by that”, “You cannot add this note to this chord”, “you must end with this chord” etc. Oh no, strangely, there seems to be some rules prevailing in music world!

Then WHEN, WHERE, by WHOM and for WHAT are these rules made?? Don’t you think it’s nonsense that someone you totally don’t know defines what the “right music” is?

Now I’d like to invite you to a brief history exploration of music theory, in order to see what the heck these rules are. You’ll get a new sense of perspective, so come with me!